UK lorry driver shortage signals a shattered job market

[ad_1]

UK employment updates

Sign up for myFT Daily Digest to be the first to know about UK employment news.

A shortage of truck drivers has led to empty shelves in UK supermarkets. There is even speak of the army called for help. For those who wanted the UK to stay in the EU, it’s like a moment to say, ‘We told you, Brexit was a disaster.’ But that misses the point. Empty shelves are a visible message from a workforce that is usually invisible. They tell a story about what is wrong with this corner of the 21st century economy – and not just in the UK.

Earlier this year Dominic Harris, who had been a truck driver since 2012, began to feel dizzy and sick. He went to the hospital, where a nurse told him his problem was exhaustion. There are legal limits on driving hours: Truck drivers can usually only drive nine hours per day (currently 10 due to shortage).

But that doesn’t mean that shifts are nine hours long. It was typical for Harris, who is 39, to be out of the house 12 to 15 hours a day. When he got home he was so tired he went straight to bed. “I lost a lot of relationships with friends,†he says. “I wasn’t the same old Dom anymore.”

Schedules can also be unpredictable. Current job offer from XPO says, “You will be working at least 45 hours per week on a ‘5-7 day’ work schedule, so your workdays may change each week and may include working on weekends. You will also start early in the morning and should be prepared to work through the night.

Despite the rough hours and the fact that they often pay for their own qualifications (Harris paid £ 1,500), the drivers have slipped up the pay scale. In 2010, the median heavy truck driver in the UK won 51% more per hour than the median supermarket cashier. In 2020, the premium was only 27%. They have faced a particular wage cut over the past five years: The median hourly wage for truck drivers has risen by 10% since 2015 to £ 11.80, compared to 16% for all UK employees. “Why would I want to be a truck driver, with all the responsibilities, the unpredictable long hours, if I can go to Aldi and earn £ 11.30 an hour stacking shelves?” Says Tomasz OryÅ„ski, truck driver and journalist based in Scotland, who is considering relocating to Finland.

Kieran Smith, managing director of Driver Require, a recruiting agency, says employers have lowered labor costs to compete for powerful clients like supermarkets. “Customers have enormous purchasing leverage [and] they nailed the transport companies to the smallest margins. He says many drivers leave in their 30s because the schedules make it almost impossible to participate in raising children, but the pay is not high enough to help the other partner stay at home.

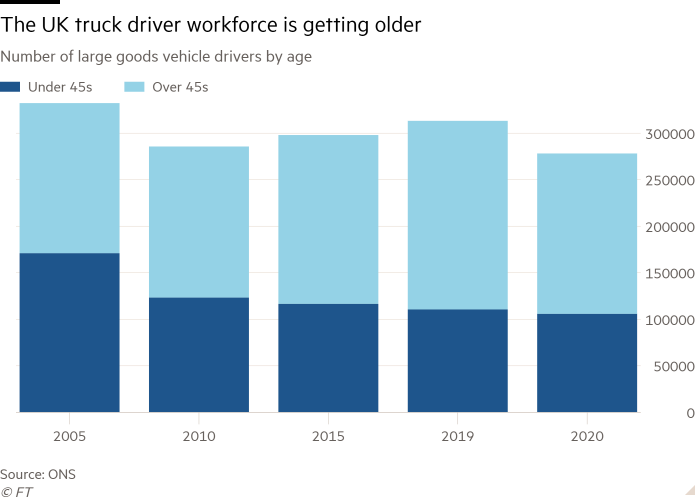

As a result, the workforce is aging. In 2000 there was a same split between those over 45 and under 45. Today, those over 45 represent 62 percent. Between 20,000 and 40,000 people take their tests become truck drivers in a year without a pandemic, but many appear to be leaving the sector. Harris left this summer to start a Business maintain graves. It’s peaceful and he loves the connections he makes. He doesn’t want to go back.

Aging workforces and labor shortages are also problems in other countries. In Europe, some Eastern European companies are dispatch of drivers work in western countries with eastern pay rates.

In the UK, the scale of the problem was masked before Brexit by an offer of European drivers who helped fill vacancies. In addition, a loophole in the UK’s poorly regulated labor market has allowed drivers to set up as limited companies. This increased their take-home pay by reducing their taxes (to the detriment of the rights of their workers). This year the government firm the loophole, which prompted some drivers to leave. Meanwhile, Covid has resulted in tests being canceled for new drivers and prompted many Europeans to return home.

Adrian Jones of the Unite union says the supply shortage means drivers now have a moment of influence. He wants to see long-term reforms like in the Netherlands, where a collective agreement is negotiated between the employer and union groups that set a floor on wages and conditions across the sector. “This collective agreement becomes law, so it gives transport providers the opportunity to tell their customers: it is the law, so I cannot find cheaper than that,†says Edwin Atema of the Dutch union FNV.

But some employers still seem determined to find short-term solutions. Tesco is offering new drivers a £ 1,000 bonus and a ‘market supplement’ over a six-month period. “All temporary inducements are at the discretion of Tesco and may be reviewed, changed and removed”, the job offer warns.

The story of Britain’s empty shelves, like that of its unpicked strawberries and unprocessed chickens, is the story of how migration, combined with a poorly regulated labor market and extremely powerful, has allowed some goods and services to become too cheap. The system saved money on our purchase invoices, but it didn’t hold up. Other voters are right that Brexit has helped provoke the current crisis, but they are wrong to say that everything was fine without it. Brexit voters are right that migration helped cut driver pay, but as the Netherlands shows, Brexit was not the only way to solve it.

Labor shortages are a time of judgment. If we just use them to bicker over Brexit, we’ll be drowning the real lessons in noise.

[ad_2]