Europe lags behind China in electric car supply chain race

Since the invention of the car in Europe 136 years ago, the industry has grown to become one of the foundations of the continent’s economic growth and prosperity.

But, as China establishes greater control of the electric vehicle supply chain, Europe’s auto sector faces one of the biggest challenges in its history as it tries to catch up.

And that won’t just mean setting up factories to make the batteries, says Emma Nehrenheim, sustainability manager at Northvolt, Europe’s most advanced battery manufacturing start-up. It will involve the entire ecosystem of mining, refining and chemical engineering needed to supply them. “Whoever has the processing capacity will be the one who controls and markets the provenance of the materials,” she says.

The EU has big ambitions for electric vehicles, aiming to phase out sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2035. This month, bloc leaders said they were planning critical legislation on raw materials to finance strategic projects and build up stocks.

However, China’s lead in the manufacture of batteries for electric vehicles is obvious. According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, it is expected to produce 76% of the world’s lithium-ion battery cells this year, compared to 7% for the EU.

“There is a lot of catching up to do,” notes Francis Wedin, chief executive of Vulcan Energy, which hopes to produce lithium, a key battery material, in Germany. “China has been several steps ahead for a while now.”

Vulcan – in which Stellantis, the automaker formed from the merger of Jeep owner Fiat Chrysler and Peugeot owner PSA, has invested 50 million euros – illustrates the challenge. Lithium is mined from hard rock in Australia and processed in China, or slowly evaporated from brines in Chile. Vulcan wants to start producing lithium in Germany from 2025 with a new, unproven technology, which pumps brine and extracts lithium directly using geothermal energy.

But, beleaguered by soaring energy bills and rising borrowing costs, leaders in Europe’s battery and raw materials industry fear the continent is becoming dependent on Asian companies, including China’s CATL, the south- Korean LG Chem and Japanese Panasonic.

Roland Getreide, director of Luxembourg-based Livista Energy, which is seeking to build lithium refineries in the UK and mainland Europe, said preparing the supply chain for soaring demand for electric vehicles is at the heart of the industry’s problems. Europe is trying to “compete with people who are already 20 years ahead with cash flow,” he says.

Even though Europe is attracting investment in battery manufacturing, executives see a big difference between Asian battery manufacturers setting up “satellite” factories in Europe supplied from Asia and a local European player buying and backing a supply chain. local supply. Last month, CATL announced a mammoth $7 billion investment in a gigafactory battery production site in Hungary.

“Battery makers from Asia moving to Europe were bringing their materials in in semi-finished or finished form,” says Mark Thompson, managing director of Australian advanced materials company Talga. It is developing a project in Sweden to extract and process graphite, vital for battery anodes.

Europe has almost no lithium and graphite operations. It is home to just one of the world’s 15 producers of battery-grade manganese sulfate and accounts for just 9% of the world’s supply of cobalt chemicals, according to critical mineral consultancy Project Blue.

European battery makers would need to bring in materials from abroad for a while, as it takes much longer to develop mining projects than battery factories. “In the beginning, you can’t avoid bringing materials,” says Thompson.

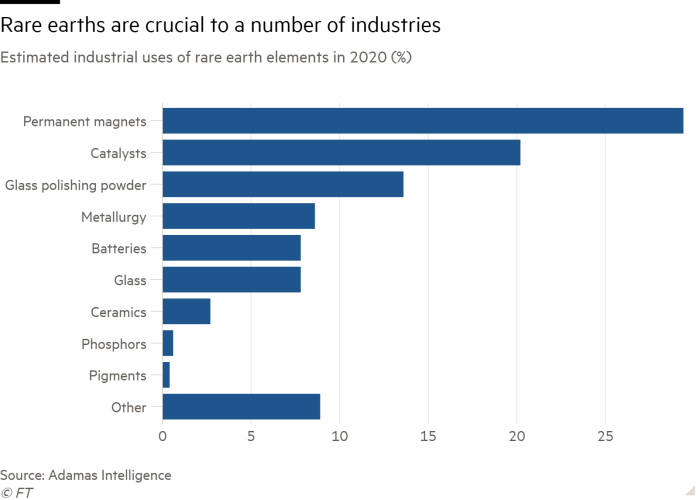

The European automotive sector also faces challenges in establishing a supply chain for electric motors, the second most valuable component of electric vehicles. These require highly specialized permanent magnets that use rare earths, a collection of 17 elements that are extremely difficult to extract and process. China dominates the production and processing of rare earths, with an estimated global market share of 80%.

Only one company in the European supply chain, the Canadian company Neo Performance Materials, is currently capable of separating rare earths for use in magnets. It holds exploration rights for a rare earth mine in Greenland, the autonomous country of the Kingdom of Denmark.

Hastings Technology Metals, an Australian rare earth miner, recently agreed to take a 22% stake in Neo Performance. But the deal is being funded by a 150 million Australian dollar investment in Hastings from a group linked to Andrew Forrest, one of Australia’s richest men – further proof that the future of the car industry Europe is entangled in a wider geopolitical and geological network.

Energy Transition Summit

Register your place for this year Energy Transition Summit to be held in London from October 17 to 19 here

See the full list of events, including upcoming ones mining summit October 20 and 21 here

Constantine Karayannopoulos, managing director of Neo Performance Materials, suggests that Europe is just recognizing the key to Chinese dominance. “What’s missing from the narrative is that China is the biggest producer of rare earths because it’s the biggest consumer of rare earths,” he says. “The magnet industry has been the driving force behind the rare earth industry.” Neo aims to manufacture magnets in Estonia from 2024, to consume its separated rare earths. GKN in the UK is also exploring building magnets for electric vehicles.

Project Blue founder Nils Backeberg says China continues to send reminders of its dominance. Last month, it increased its annual quota for mining production of rare earths, which Beijing uses to control prices, by 25% to a record high: “It again underlined that China holds all the cards.

Comments are closed.