Ads with unregulated climate claims are a barrier to real emissions cuts – NGO lawyer

What elements of the proposed update to the EU’s Unfair Consumer Practices Directive are likely to be most helpful to activists suing companies over false climate claims?

The committee has proposed a veritable series of anti-greenwashing amendments that will make their way into EU law and then into member state law. I think there are three things I would take away from the new European legislation that are particularly relevant to the issue of climate transition and corporate advertising.

The first point is that the reforms explicitly place environmental and social impact (as well as durability and reparability) on the list of key product features, which, if untrue, could be a misleading and contrary business practice. to the law. This reform sends a very important signal: misleading on the environmental impact is just as illegal as misleading on the price of a product.

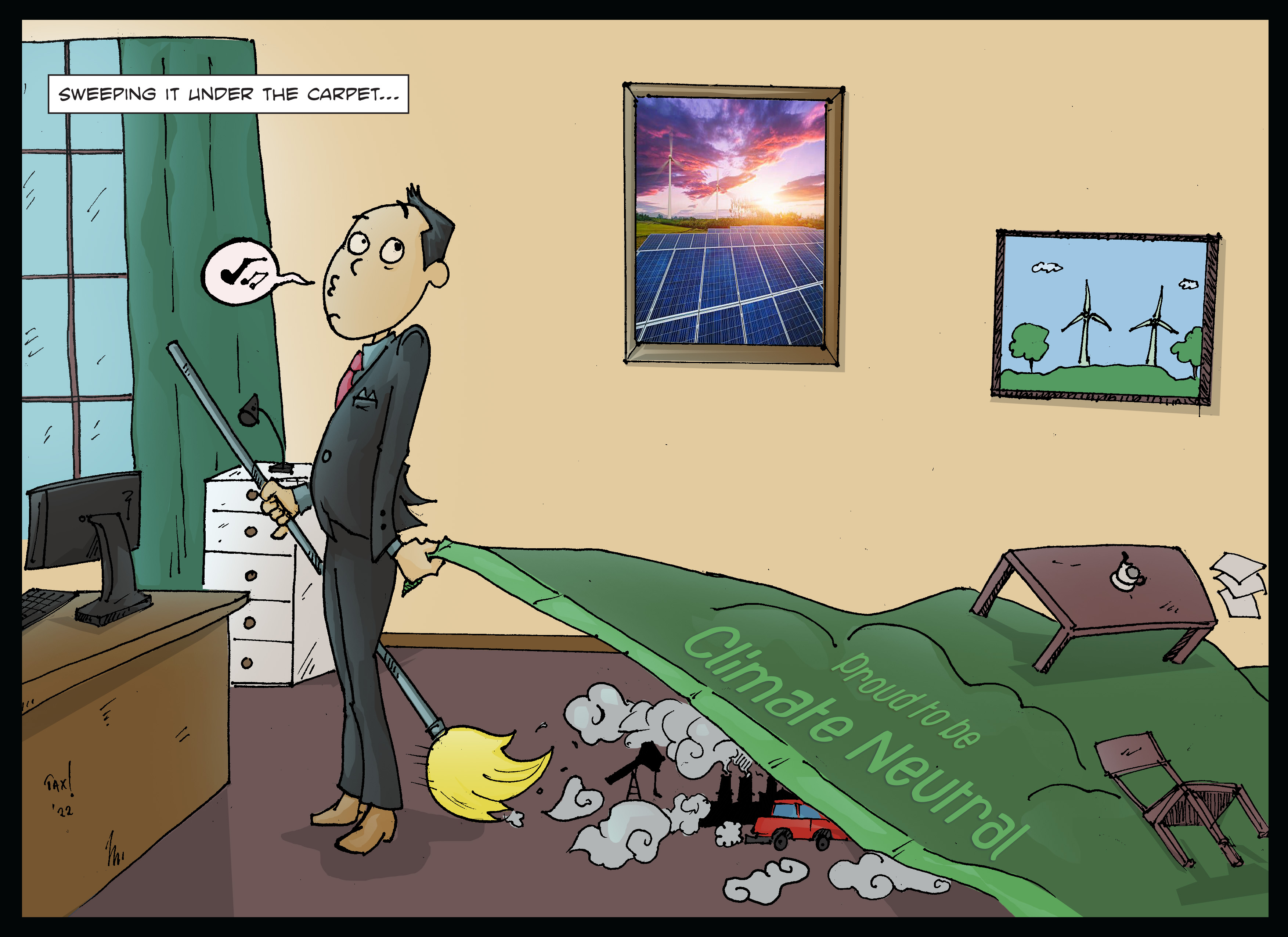

The second concerns vague claims. To help enforce the ground rule that environmental claims must match environmental evidence, the reforms specify that “generic environmental claims”, such as “eco-friendly”, “green” or “biodegradable”, will considered to be in breach of the law, unless it is a product of the EU Ecolabel scheme. People have a right to accurate and meaningful information about the environmental impact of a product or company. This reform is key to making the “sustainability hype” a thing of the past through legislation.

The above two points apply to any environmental claim a company might make. Often sustainability claims are not about specific products but about the company itself and these points are relevant both ways.

The last point concerns future objectives. This specifically distinguishes marketing claims about future environmental performance, such as “net zero by 2050” or “100% recycled plastic by 2030”. These claims are too often promoted without any valid basis and not seriously pursued. Now companies marketing these goals will need to back them up with clear, objective and verifiable goals and commitments – and progress against these needs to be verified.

It is important to note that all of these reforms are in our view not changes to the law, but a clarification of the existing general rule that companies cannot mislead the public – which fully applies to climate claims. in advertising.

Why is the European Commission proposing these updates to existing legislation?

It does this to protect, inform and support consumers. The European Commission itself says the updates are designed to strengthen consumer rights so they can actually make informed choices and play an active role in the transition to a climate-neutral society. Essentially, this is to ensure that consumer law is also about reducing emissions. The transition involves a change in consumer behavior as well as in business production.

There is a desire to correct the greenwashing market. The commission identified a large number of potentially misleading environmental claims. In a survey, they found that 40% of green claims online were potentially misleading in 2021. So they are trying to establish and strengthen the law on these issues to correct this developing market failure, because if people don’t don’t have the right information, there’s no way we’ll make these changes in the time we need.

Why are ClientEarth and other organizations calling for an outright ban on advertising by fossil fuel companies?

The quickest and most effective way to stop the greenwashing of these highly polluting companies from interfering with the energy transition is for lawmakers to treat them like Big Tobacco and ban their advertising.

As we see, there is simply no argument for maintaining or increasing the role that these fossil fuels and high-emitting products and goods play in our society, so why do we need publicity to them ?

The alternative to a ban is that we simply allow existing law or general principles to have their effect and hope that ordinary consumers, regulators and civil society are able from time to time to enforce the law against these practices and try to stop the problem in that way. The problem is that we just don’t have time for it.

You could take the example of natural gas at home. According to the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Scenario globally, we need to phase out the use of natural gas in home heating by 2035. In Europe, this should be faster because the Europe obviously has more capacity than somewhere like East Africa. And that means the changes have to happen now.

Advertising that promotes gas or companies that supply it in volumes that do not meet these targets obviously acts as an inhibitor. This is why there are so many movements for a ban on fossil fuel advertising.

We started to see regulators react. We’ve seen the news of the French ban come in and the city of Sydney may soon join the city of Amsterdam and a slew of other local governments in banning fossil fuel ads. I think it’s something that won’t go away.

Do you see any positive arguments for giving companies some leeway in terms of communication? Could this help companies attract green investment, for example?

This is the argument often advanced against the idea of a ban. But the point is that we have to think about what the ban is about, which is advertising. So this does not and would not affect product availability. It would certainly not affect the availability of funding from the banking sector or even the information provided to shareholders for investment purposes in all their corporate filings. And so I don’t really see that affecting those things. It would be nice to think that we could give companies the ability to aggressively move away from fossil fuels and then communicate about it while they do it. The problem is that climate change and the link to fossil fuels and risks have been known since at least 1988, and they haven’t. Instead, advertising has become this great inhibitor of real climate action and the transition that we need. So, unfortunately, the clearance case looks like a real risk. You have to ask yourself again: what harm is really done by removing the tools of societal influence that fossil fuel companies have when we know their products are things we need to eliminate or dispose of?

Comments are closed.